Bee & ThistlE Winemaker Notes

Winemaker Introduction (March 12, 2019)

My name is Margaret MacInnis. I am the Winemaker at Bee & Thistle Winery. I completed the UC Davis (University of California) Winemaker Certificate Program in March, 2019 with honours. The studies began in September 2017. The modules included:

Introduction to Wine and Winemaking - completed December 2017

Wine Production - completed March 2018

Wine Stability and Sensory Analysis - completed June 2018

Viticulture for Winemakers - completed December 2018

Quality Control and Analysis in Winemaking - completed March 2019

The courses were intense; they were delivered online with weekly lectures in the ZOOM platform where we met with the instructor and classmates. Transferring all the knowledge from winemaking with grapes to fruit winemaking was a challenge I was prepared to face! In addition, several instructors helped during the adaptation phase. I am excited to venture into fruit winemaking with Haskap and Rhubarb and add other fruits as they become available.

Margaret, Winemaker, Bee & Thistle Winery Inc.

Why do Yeast Make Ethanol? (March 13, 2019)

The short answer is because they can.

Don’t for a second think that yeast have brains and that they are producing alcohol for our benefit! The truth of the matter is, the ethanol is a by-product of a food system that allows yeast to grow, make energy and reproduce. Yeast belongs to the Fungus Kingdom. They are a single cell and generally reproduce by budding. During their life processes, they basically spit out ethanol and carbon dioxide as they process their “food”, which is sugar. The series of reactions are chemical ones.

Happy yeast produce ethanol from the sugars in our fruit, and you’ll be happy they did!

Ladybugs: Friend or Foe? (March 14, 2019)

The ladybug was first introduced to North America during 1916 from Asia (Japan and Korea). They are actively sold and marketed as a form of biocontrol against aphids and some small soft-bodied pests. One can purchase thousands of them for this purpose. While it has proven very efficient in certain pest control, MALB (multi-coloured Asian Lady Beetle) adults can accompany the fruit on the harvester and subsequently be transported on fruit to the winery; this is not an ideal situation. Unfortunately, if ladybugs are present during winemaking operations, they can produce off-aromas and flavours in the wine known as ladybug taint (LBT). Chemically, the taint is produced by an order of compounds defined as methoxy pyrazines, which isn’t of interest to most people, but Winemakers tend to be fussy about it!

Whilst Bee & Thistle Orchards encourages the proliferation of ladybugs to control aphids (particularly on Black Currants and garden vegetables), we conscientiously sort wine-destined fruit at the conveyor belt and washing stations; we don’t kill them but return them to the gardens as much as possible. We do not see more than one or two ladybugs per 100 pounds of fruit, and they are easy to spot and sort out. So, yes, ladybugs are both friend and foe. It depends on what you are growing or making. But we won’t be purchasing any for deliberate pest control anytime soon.

Wine Acids (March 26, 2019)

Since we are making fruit wine, as opposed to grape wine, the consideration of acids will be different for each fruit. Grape juice or must (must is the juice and fruit parts before it is fermented completely) contain both tartaric and malic acids, with lesser amounts of citric and other minor acids. Usually, this is predictable, depending on the grape variety, and Winemakers adjust to get a certain pH, and a certain level of acid in their finished wines. This is done by strategic actual additions of either extra acid (usually tartaric, or maybe malic and/or citric) or, if the acidity is too high, the extra acid is neutralized by additions of an alkaline product (such as calcium carbonate).

So, you may ask, what do acids do?

Acids affect the taste profile of your wine. Think of a lemon, or even an orange. Both are high in citric acid, with the lemon being very high, and it gives your mouth a brisk, clean feeling. The orange is also high in natural sugar, and has slightly less acid anyway, but the sugar makes the acid taste less acidic, and your mouth reacts in the expected way. If you’ve ever had sweet and sour sauce, which is a combination of acid (vinegar is high in acetic acid) and sugar, it’s a pleasant taste if combined properly in the right proportions.

Each acid promotes a different mouthfeel and taste to the wine. Malic acid is rather harsh (green apples are very high in malic acid), so many Winemakers choose to convert malic acid to lactic acid (the acid of milk), giving the wine a smoother, almost buttery feel and taste. Tartaric acid, in the correct proportion, is very beneficial in accentuating the other flavours, aromas and tastes of the wine.

At the time of writing this post, I am studying the composition of the fruits I will be using to make wine.

Our signature fruit is Haskap.

Studies have been done to determine exactly what acids Haskap contains. Depending on the cultivar, the main acids of Haskap are Citric, Malic and some Quinic acid. Because most fruits (other than grapes) are so high in natural acids, higher than what would taste good in wine, Winemakers dilute the juice with water; natural Haskap has a sugar that would ferment to about 8 or 9 % alcohol but, remember, we must dilute that, so without the extra addition of sugar, our wine would not have the desired alcohol.

Screw Caps Versus Corks (April 2, 2019)

This post is to discuss the relative merits of screw caps versus corks. Exploring the relative merits and pitfalls of each is a very difficult discussion.

Primary is consumer acceptance and expectation, which also often includes a little misinformation and pre-conceived ideas on what corks can and can’t do, and what screw caps can offer.

Corks

Corks have a long-standing history, and generally will be well-received by most customers. In fact, consumers have been polled, and it has been found that most consumers believe better wine is always corked, not screw-capped. Why is this true? Well, corks are traditional. If you go to a discerning establishment, they often hand you the cork - and many people have no idea what they are supposed to do with it - look at it and judge it somehow ‘okay’….

In truth, the factor they are supposed to be looking for isn’t something they can visually test; to achieve some measure of validity, you must SNIFF the cork and see if you can detect some mousy, harsh moldy notes. You must also sniff and taste the wine for evidence of cork taint, which is the issue you are being called upon to judge.

What’s ironic is that not all people can even smell or detect low levels of cork taint, which is caused by levels of TCA in the wine (TCA is short for tricholoroanisole, a chemical produced by the reaction of wine with cork that has some mold factors in it). How many corks and bottles of wine will be affected? Some say as many as 5%; others argue one bottle in 100. At any rate, just because one bottle in a vintage has the cork taint does not mean they all will. But again, not all people detect the presence of TCA at low levels, and some can’t smell it at all!

What else do corks do? Well, the main thing they do is give the consumer an ‘experience’ that they like. Many people like the ritual of removing the capsule, taking out the cork, and pouring the wine.

Corks also allow a very small of oxygen in over time, which is said to age the wine gradually, through a series of chemical reactions. There are some modern-produced corks that are partially synthetic, and these will not have the TCA reactions. They are, however, quite expensive.

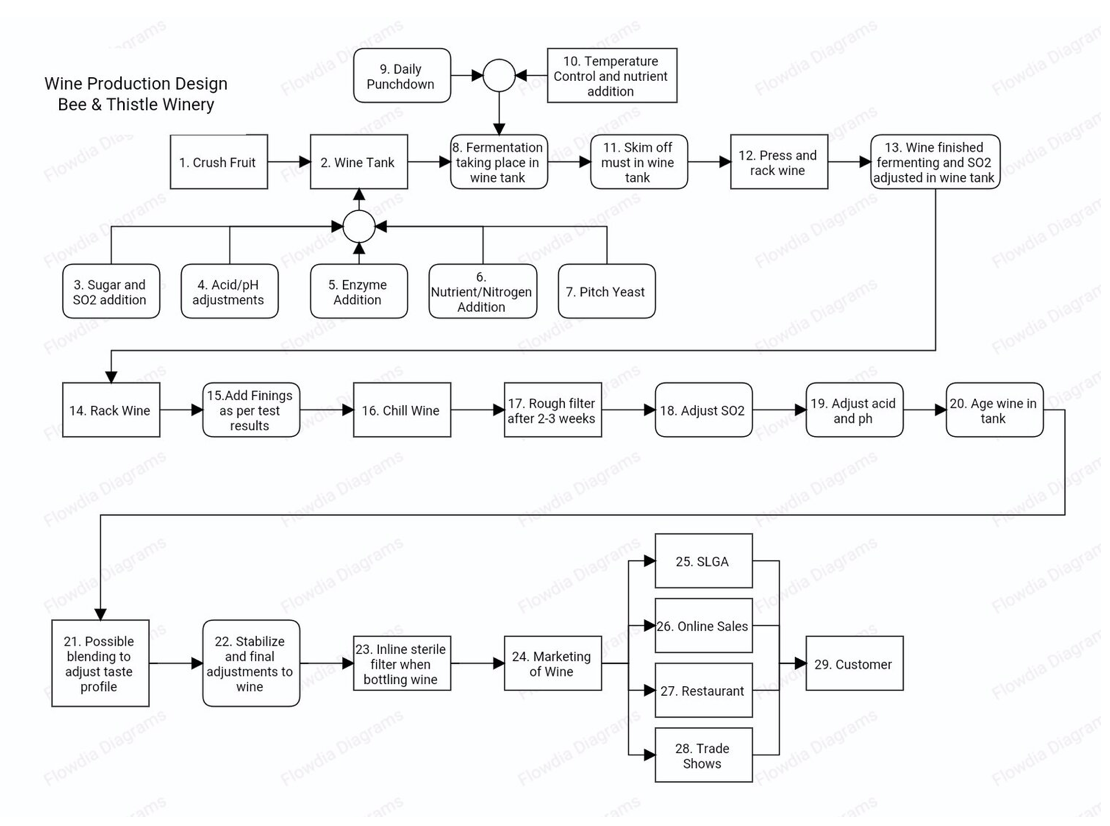

Introduction to Wine Production Process Design (April 9, 2019)

Please note all design elements and information given is copyrighted c. 2019 Margaret MacInnis

One requirement to obtain our manufacturer’s license is to submit a Process Design folder which outlines the steps we will be taking to make wine. The information below is part of our Policy and Procedures and is meant to detail (without going into winemaker specifics) the various steps required to produce a top-quality wine.

Winemaking is a biochemical process that has evolved for many thousands of years. In its most basic form, yeast catalyzes a series of reactions to ferment the sugar from the input products resulting in ethanol in the wine and carbon dioxide which escapes to the air. The main processes include harvest or obtain fruit, fruit crush, amend and chaptalize, fermentation resulting in ethanol/wine, correct chemically while settling and stabilizing, rough filter, stabilize again/correct/tank age and, ultimately, package/sterile filter, (store and age) and deliver to the customer.

Significant instability often occurs during the production of wine. Control strategies will be implemented such as input of quality products (fruit, sugar, yeast, amendments), specific lab testing/analysis of individual components and processes with adjustments (including monitoring of temperature, bacterial contamination, adequate fermentation progress, taste and appearance, among others).

Method of Wine Production From Flow Chart

The flow chart indicates each of the major steps from crushing the fruit to wine reaching the customer. This is the ideal wine production design module. At all stages, adequate cleaning and sanitization of equipment is assumed, which is a process in and of itself.

*please note that chemical terms (such as SO2) are subscripted in technical materials

Introduction to Wine Production

The wine production system is complex because of the number of sequential and parallel biochemical and physico-chemical reactions. In its most basic form, production of wine/ethanol can be represented by the chemical formula:

C6H12O6 ====> 2(CH3CH2OH) + 2(CO2 ) + Energy (which is stored in A

*yeast* These reactions occur in the yeast cells during fermentation, releasing products

In simplest layman’s terms:

Sugar is digested by yeast ====> Alcohol + Carbon dioxide

(Glucose & Fructose) (Ethyl alcohol or Ethanol) (Carbon dioxide released to air)

Before fermentation begins and during fermentation/stabilization, steps need to be implemented to create a quality product (wine) which will be marketable, palatable, safe, and fall within the parameters of acceptable ABV (alcohol by volume) and food safety as outlined by SLGA and CFIA (Saskatchewan Liquor and Gaming Association and Canadian Food Inspection Agency).

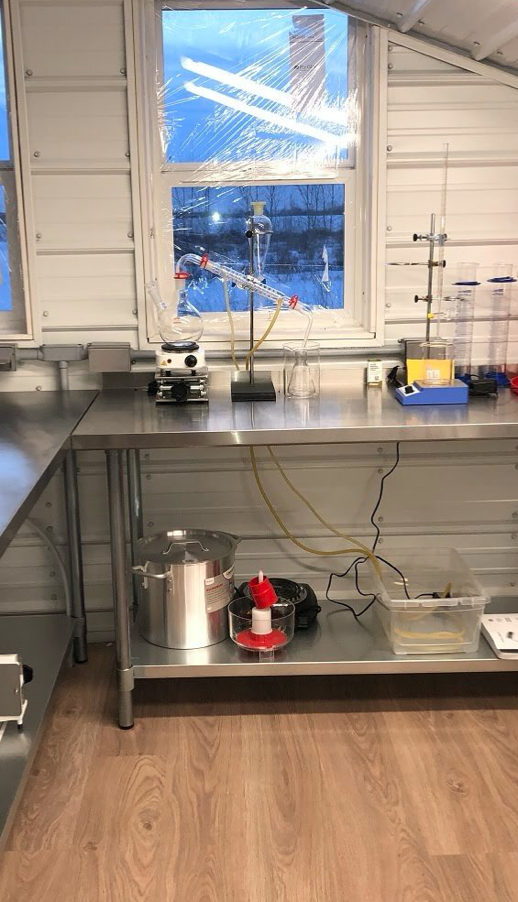

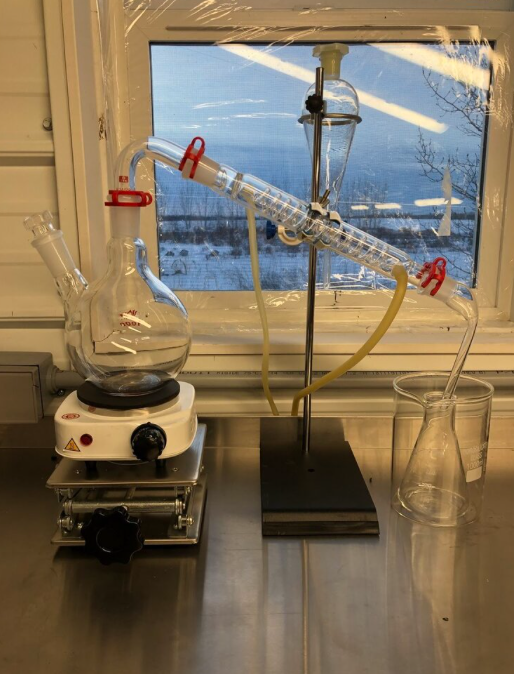

Alcohol by Volume Using Distillation/Hydrometry Technique (March 4, 2020)

One of the myriad of lab tests taught at UC Davis was the ABV (Alcohol by Volume) using the bench distillation apparatus followed by hydrometry. The principles of distillation are universal; essentially, you are using the concept that alcohol and water solution behaves differently from either pure alcohol or pure water (called an azeotrope in the language of chemists and distillers) alone. Alcohol and water solution boils and vaporizes much sooner (less than 80°C) than water alone (100°C). This allows the alcohol and water in the wine mixture to “boil off or vaporize,” leaving the residue in the wine flask behind. This residue would have interfered with the subsequent hydrometry test.

If you look closely at the photo on the right, the Graham condenser is the long-angled tube with the little spring-shaped glassware in it; the condenser allows the vaporized solution to condense back into a liquid which falls into the little collection vessel on the right. Why does it condense? During the vaporizing and boiling process, ice cold water is pumped through the condenser’s yellow tubing from the ice water basin hidden under the table. There is a small aquarium pump in the ice water. The ice water effects the condensation of the vaporized alcohol and water, and the condensate (also called distillate) drips into the collection beaker on the right. To better understand this concept, think of boiling water on the stove. If the steam from your soup pot hits the colder cupboard above, it will form droplets that drip back onto the stove or into the pot.

After the distillate is collected, the next step is to bring the level of the distillate back to the same volume of wine you started with by adding enough distilled water. For example, if you started with 250 ml of wine, and collected 200 ml of distillate, you would add back 50 ml of distilled water. This works because at that point, all the alcohol is distilled out along with only some of the water and to create a situation of equal measure, you must equalize the solutions. And at that point, you no longer have the issue of the other wine components interfering with the delicate hydrometry test.

Then you measure the alcohol by volume with a special instrument called an ABV Hydrometer. The hydrometer is based on the principles of density; there are special ones with a narrower range and wider bulb for accuracy. Essentially, you are measuring the density and then using tables to convert to actual ABV, expressed as alcohol v/v or alc/vol. There are also instant calculators that will allow you to input the measured density, and they will calculate the ABV for you. In Canada, the Excise department accepts only certified calibrated instruments for the purpose of density hydrometry testing. We also had to purchase a certified thermometer to determine the temperature of the final distillate. In addition to the ABV tables, there are also “temperature correction tables'' to adjust the density reading if the temperature is not exactly 20°C. The final ABV is what will be written on the bottle. Initially, we are required to verify this reading by an independent laboratory, but once we prove that we can accurately determine the readings, we will be permitted to conduct the test without verification.

Bench Trials in Winemaking (April 29, 2020)

A Winemaker does their experimental lab work on a lab table; historically, Winemakers used a bench beside their fermenters. Those tests have become known as bench trials. The purpose of a bench trial is to test various combinations and quantities of additions to determine the best one.

Test and Control Flasks - Addition (front flask) diluted in a scaled-down fashion as described below

There are various steps required to complete a bench trial.

We first take a larger sample from each test batch, divide it up into smaller equal amounts. For example, if I want to trial a bit of a specific addition, I will take 500 mL of juice from Batch 2 and divide into 5-100 mL flasks,

I will add progressively larger amounts of the addition to each flask on a scaled-down basis; for example, these test flasks will receive (scaled down), 10.0 to 20.0 g/HL, in increments of 2.5 g.

Sensory Analysis: See below. I can determine the final addition amount that will give the appropriate result. This amendment provides astringency and a little body to wine. We do this analysis blind. In other words, neither I nor my taste tester will know which analysis cup has which addition amount.

Colour: Although the amendment to stabilize colour will not fully develop for months, it will give me a guideline to follow. The amendment combines with colour molecules called anthocyanins to stabilize them and make them less prone to breaking apart. If the colour molecules break apart, we will turn our wine from a nice deep desirable red to a less pleasing washed-out red. The goal of colour retention in Haskap is particularly important, as consumers expect and believe a more highly coloured wine is of higher quality (this theory has been proven again and again in taste tests). By its very nature, Haskap juice does exhibit an intense colour, and we want the wine to reflect this potential.

What do I mean by scale-up and scale-down?

Scaling-up: is an increase according to a fixed ratio. It can be described this way - if I have 1000 L, and the instructions say ‘add 10-20 g of the amendment per HL, I will add 100 g to 200 g per 1000 L since 1000 L is 10 times 1 HL. (1 HL or hectoliter is 100 liters).

The paper was .24 g, so we weighed 1.24 g to get 1.00 g in the end. This was added to the water in the dilution flask.

Weighing the Amendment - The paper was .24 g, so we weighed to 1.24 g to get 1.00 g in the end. This was added to the water in the dilution flask.

Scaling-down: is a laboratory method of adding test variables to a rather minuscule amount of wine on a ratio basis. I’m working with really small amounts, and I must do a little math. Plus, to do a scaled-down addition with the amounts being so small, I also must mix the measured amendment with a larger amount with water and pipette out a mathematically determined amount, because I don’t have the means to weigh such a small quantity (I’m talking fraction of a milligram, which itself is 1000th of a gram).

The math would be calculated like this:

Instructions: add 10-20 g per HL.

Amount per 100 mL is incredibly small as you convert grams to mg. I therefore need 10 mg in 100 mL. 10 mg is an amount that is difficult to accurately measure by itself. To compensate for that difficulty, I mix a larger amount with some water and figure out how much is in it. Knowing I can weigh out a gram (1000 mg), and add it to 100 mL of water, I can finish with 10 mg in each mL mixed solution. I have pipettes that can pipette down in increments as small as 0.10 mL, so doing the following task is not impossible.

I’ll be putting progressively larger amounts of the amendment/water mixture in each flask. Remember I have 10 mg in each mL of mixed solution.

Flask 1: the control has no additions

Flask 2: 10 mg or 1 mL of the mixed water and amendment solution

Flask 3: 12.5 mg or 1.25 mL

Flask 4: 15 mg or 1.5 mL

Flask 5: 17.5 mg or 1.75 mL

Flask 6: 20 mg or 2.0 mL

Step 3: Sensory Analysis (including colour, aroma, taste, mouthfeel, body); a pretty good baseline for starting our additions should be obtainable. First, we compare A to B. Rinse mouth, and compare the ‘winner’ of A and B to C. Repeat down the line. The current comparison is for mouthfeel (including body and astringency) and colour. Ideally, we would have taste-testers but in this current environment, we must rely on our own perceptions. Both of us agreed that the lower addition rate of 10 g/HL had the most promising result, so we added that to the test batches yesterday.

Tasting cups are randomly labeled for blind sensory analysis

Brix - How Sweet It Is... (April 19, 2020)

Brix, or degrees Brix (°Bx), is defined as the number of grams of sugar in a measured weight of solution. 1°B or °Bx is 1 g of sugar in 100 g of solution or 10 g of sugar in 1000 g of solution (about one liter). Fruit inherently possesses some sugar, with only grapes having enough natural sugar and acid ratio to make wine directly without amending. Haskap fruit is too high in acid and too low in sugar to make wine without first diluting it with water and, secondly, adding sugar (the winemaking term for adding sugar is called chaptalization).

Yeast use sugar to make alcohol during their life processes. So, if you know how much sugar you have in your juice (or how much you added), you can approximate how much alcohol you can expect to be rewarded with at the end of fermentation. We measured Brix the first time before we pitched the yeast and found it to be 23 °Bx. This means that each 1000 g of solution had about 230 g of sugar.

The measurement of specific gravity relative to water of the juice (specific gravity is the solids and such in your mixture) will be done with a hydrometer, and if the hydrometer is not marked in degrees Brix but a different scale, then you can use an equivalency chart to know what the number is. The hydrometer is photographed below in the measuring container which holds the fermenting strained juice/wine. It is measured in degrees Brix (°Bx).

The hydrometer is a very sensitive piece of equipment; well-balanced hydrometers that are certified by Science Directorate in Canada will set you back about $200 each (a requirement of Excise Canada) but, for daily use, a less expensive one will suffice. The ones we purchased were about $35 each and we are very careful with them. The SEDs are reserved for final alcohol calculations; they are not generally used daily.

The photo below shows a reading of 17.6 °Bx, read at the bottom of the meniscus (the meniscus is the lower part of the curved liquid made at the surface). From that, we calculate the progress of our fermentation, subtracting the reading from our initial reading (which was 23 °Bx). So we have used up 23 - 17.6 or 5.4 (°Bx), or 54 g of sugar in a liter of the fermenting wine. From that, we multiply by 0.55 or so, and approximate that our wine is now at about .55 x 5.4) or 3% alc/vol. We started with about 230 g of sugar in each liter of juice with the intent of making approximately 12.5% to 13.5% alcohol, written on the bottle as % alc/vol.

Many Winemakers use either Oechsle or Baumé scales instead, but the process is the same and just the numbers vary in how they calculate the same % alc/vol.

Reading of 17.6

°Bx - This is verbally stated as 17.6 degrees Brix

Sugar Choice

Because we were adamant from the beginning that all products used for actual fermentation be Canadian produced and acquired, we have chosen to use Taber Beet Sugar from Alberta, Canada. Since sugar beets are grown and processed in Alberta, Canada and sugar cane is imported, the choice was easy. The Taber Company identifies their Beet Sugar by starting their lot number with 22, notable in the photo below.

Acid Balance: Focus on MLF (April 30, 2020)

Options for Acidification and De-acidification

1. Dilution for De-acidification

Grape wine: Dilution with water is not an option for most professional Winemakers although it is dictated by country and regional wine appellation rules. Therefore, most grape Winemakers will choose to blend or use other methods of increasing or decreasing acidity.

Fruit wine: It is generally acknowledged that fruit juice/fruit will require dilution. Fruit Winemakers spend many hours calculating the correct ratio of fruit juice to water in order to achieve a stylistic acid balance. Each batch of fruit will have a different ratio which must be independently verified every time and is often a well-kept secret. Also, different varieties of the same fruit are treated differently; again, a Winemaker’s diary and secrets of the trade as to how we manage those.

2. Natural Fruit Acids for Acidification and Chemicals for De-acidification

Some fruits and many grapes (particularly cold climate grapes) require further amendments to obtain a desirable acid balance.

Acidification: Generally speaking, acidification with tartaric and/or malic acids is considered acceptable in both grape and fruit wines. Depending on country and regional appellation rules (and good wine making practice), citric acid may be used as well, although it is often banned. For example, bananas are very high pH with low acid level and will require some acid adjustments at crush. A Winemaker may choose to use tartaric, malic, or citric acid (or a blend of any of them). All acids used in amendments for winemaking are usually obtained from natural fruit sources, and not chemically or artificially produced.

De-acidification: Two major chemicals used are potassium (bi)carbonate and calcium carbonate. Used correctly, this is a powerful tool in the Winemaker’s arsenal to achieve acid balance. Again, bench trials will be necessary. The specifics of de-acidification are lengthy and beyond the scope of general discussion. Courses are available if you would like to learn more.

3. Malolactic Fermentation for De-acidification (MLF)

Malolactic Fermentation uses safely isolated bacteria found naturally in fruit and wine providing a species that will do the job of secondary fermentation without creating undesirable effects. For example, Oenococcus oeni is one of the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) which converts malic acid to lactic acid. In other words, if Malolactic Fermentation were allowed to progress ‘naturally’, the wine could develop several faults due to the action of undesirable LAB strains. We have chosen a specific commercial strain of LAB. There are many strains of LAB available which, like yeast, provide for specific secondary attributes and are chosen based on the stylistic goals of the Winemaker.

Complete: Grapes and most fruits have at least a measure of malic acid in them. Malic acid levels will depend on variety, ripeness, climate variation and sunshine hours. Haskap have approximately 40% malic acid which can be changed through the action of malolactic bacteria to lactic acid, if desired. Lactic acid is often more desirable since it is less acidic, creates a smoother taste profile, and may assist in achieving the stylistic goals of the Winemaker. Often, a wine is put through a complete MLF during which all the available malic acid is converted into lactic acid. In saying so, MLF may create other attributes, such as a buttery profile which detracts from the fruit-forward character of Haskap wine. There are, however, methods of conducting MLF which decrease the undesirable attributes and accentuate the desirable ones.

Partial: Winemakers have the option to conduct a partial MLF in an effort to balance the taste profile. In other words, only part of the malic acid will be converted to lactic acid; when the desired profile is obtained, the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are halted by one of several means, including filtration. I have chosen to attempt a partial MLF on Batches 2, 4, and 6. MLF is a lot less aggressive and takes longer than yeast primary fermentation. The bubbles are tiny. There are more parameters to monitor as well, but we’re hoping the result will be worth the effort.

Batches 2, 4 and 6 will undergo partial MLF

4. Blending

Many wine batches have been saved by judicious blending with another of higher or lower acidity. Again, Winemakers use bench trials to make these decisions. For example, if the titratable acidity (TA) of batch A is over the top (e.g. 11 g/L), and batch B is relatively low (e.g. 6 g/L), one could blend at a ratio of 1 part batch A: 4 parts batch B, in an effort to achieve a more palatable TA of 7.5 to 8 g/L. Since wine is an incredible buffer, the chemistry of this blend will not work out mathematically as one expects. Therefore, bench trials are in order.

New Terms

Appellation: An appellation is a legally defined and protected geographical indication used to identify where the grapes for a wine were grown. Many countries have dozens of appellations. The term is not used for fruit winemaking.

Buffer: The property of a substance to change the pH in ways you don’t expect or can’t mathematically predict due to the nature of that substance (weak acids and conjugate bases in the same solution or weak base and conjugate acid in the same solution). By its nature, wine is chemically very unpredictable and frequently buffers blending.

Testing the Winemaking Process (May 3, 2020)

Follow along as our Winemaker, Margaret, and our CEO, Peter, walk us through the winemaking process. They created several test batches to check each of the winemaking steps.

Introduction: Test Batches

During the winemaking process, many variables can be adjusted to allow full expression of the potential characteristics of the fruit. Your perception of a wine is affected by aroma, body, mouthfeel, acidity, colour, alcohol percentage and sweetness. Throughout the winemaking process, these characteristics can be expressed more fully or tempered to allow for a balanced and complex product. Follow as we conduct many test batches to check our procedures and solidify a plan of action for the large tanks and primary fermenters.

The following photos show the orchards in full flower and then netted to prevent the birds from eating the Haskap berries.

Day 1: Primary Preparation: Test Batches

Pitching the yeast is probably the most exciting part of the journey as any Winemaker can attest to. After the berries were crushed, tested, amended, allowed to settle a bit and divided into 6 separate test primaries, we pitched the experimental yeasts. For the first set of tests, we used 3 separate yeasts. The front primary of each twin set of buckets is a ‘control’ and the back primary is the experimental bucket for additions. By the next day, all six should show some activity indicative of early fermentation. The time before the yeast begins multiplying is known as the lag phase, and it can be prolonged for various reasons. Then the yeast multiplies exponentially during the log phase. Once the yeast multiplication reaches a crucial level, it will begin to transform sugar into alcohol.

What is a primary? Referred to in the winemaking world as the primary fermenter, or where the business of alcohol fermentation begins. Since this is a messy business with a lot of foaming and CO2 production, primary fermentation is usually initiated in open top containers to allow for twice daily punch down and quality checks. It is at this time that the Brix (sugar/density check) and temperature are graphed to ensure fermentation is progressing properly.

Day 2: Daily Maintenance and Progress Reports: Test Batches

Daily maintenance of the wine now involves punch down 2-3 times a day. One of the by-products of the fermentation process is C02. As it escapes, the fruit solids rise with it. The solids in the cap also happen to contain most of the colour, aroma, and body characteristics of the wine, so we want the liquid to be exposed to them to expedite their extraction. We also check the temperature and the Brix.

We also check the titratable acidity of the wine which will give us the approximate acid content. Too high a pH creates an environment in the wine we don’t want. We also don’t want our wine to be too sour or too flabby, so getting these numbers correct from the beginning will perfect the balance we are looking for.

Day 3: Measurements and Decisions Based on Bench Trials: Test Batches

Once a day we check the Brix (density of sugar remaining), the temperature and pH of each test batch. The temperature needs to be controlled - if fermentation runs too hot, the yeast will die; if the fermentation runs too cold, it will slow down and may even ‘stick’. A stuck fermentation is the bane of every Winemaker’s existence (except maybe for fruit flies).

All three parameters (Brix, temperature, and pH) are graphed daily, giving a visual representation to monitor each batch’s progress and take corrective action as required. Acidity (titratable) is measured less frequently, but it is a good indicator of one of the more crucial parameters Winemakers consider when assessing wine and fruit.

The following video shows what Haskap looks like during the fermentation phase.

Days 4 - 7: Fermentation: Test Batches

The next phase consists of doing thrice daily punch-downs and once daily Brix, temperature and pH assessments. These three parameters are monitored until the wine ferments to dryness, or all the available fermentable sugar is processed, and all the potential alcohol is formed. Adjustments are made according to all tests and parameters, including visual.

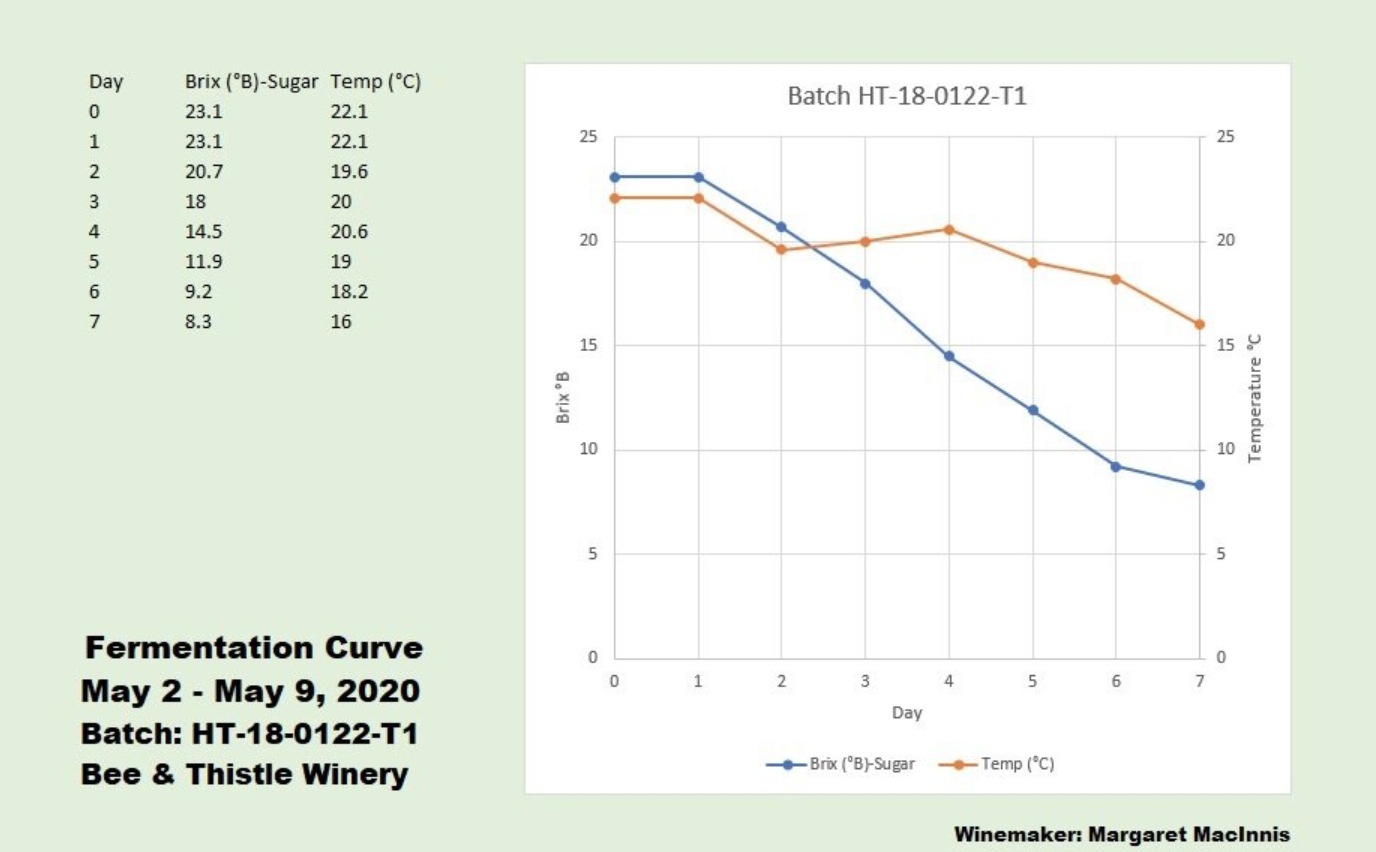

The following is an example of a Fermentation Curve, graphed in Excel. Visual representation makes it easier to see progress and understand if things are going wrong so they can be fixed before they cause bigger problems. Winemakers learn to interpret these graphs and figure out when the expected curve is veering and will quickly run an assessment to figure out why. Many reasons exist that could possibly skew the curve or even cause stuck fermentation. This is not an exhaustive list, but it gives you an idea of how we trouble-shoot Fermentation Curves that aren’t doing what they are supposed to.

The time before the yeast begins multiplying is known as the lag phase; in this graph it is represented by the straight line from Day 0 to Day 1 and it can be prolonged for various reasons. Then the yeast multiplies exponentially during the log phase (Days 1-6). Once the yeast multiplication reaches a crucial level, it will begin to transform sugar into alcohol. At the end, from about Brix 10 or so (from Day 6 on the graph),the yeast cells slow their multiplication and fermentation slows a bit. At this crucial point, it is important to track the curve carefully, observing for evidence that the yeast is not nourished correctly, and taking action to provide the required nutrients in the proper format. Studies have been conducted many times which allows Winemakers to use the data to amend the must appropriately so that fermentation continues to completion.

Day 7: Pressing: Test Batches

Please follow the video for a more detailed visual representation of the pressing process.

Decisions: The decision to press is governed by the Winemaker’s stylistic goals and laboratory testing; sometimes the results of testing indicate that action must be taken earlier than later. The original intent for this wine was to continue berry maceration past the end of fermentation (called extended maceration). Because the acidity was rising and creating a tart taste, and the skin components were adequately extracted, the decision was made to press on this day. The acids can be adjusted somewhat, but over-extraction of skin tannins and other variables would give a somewhat harsh and biting character to the taste profile. In this particular case, it was decided to use the free run going forward, reserving the press fraction for later use as it has too strong a profile for the stylistic choice.

The Press: The winery has an 80 L bladder press which was sanitized and assembled on a pallet. The receiving bucket is at the end of the funnel at the base of the press. The water hose is attached to the inlet and there is a gauge monitoring the pressure of the water in the bladder.

Pressing Terms

Bladder Press: inside the press is the vertical brown bladder which is connected to a hose. A pressure gauge monitors the pressure of the filled bladder as it presses the berries against the sieve side of the press, extracting the juice/wine.

Free Run: this is the juice/wine that runs freely with no pressing.

Press Fractions: this is the juice/wine that runs after pressure is applied. Large scale Winemakers will even do several press fractions, one at lower pressure, and some at increasingly higher pressures, switching the receiving vessel between pressure gradients to obtain specific press fractions that will be used for different purposes such as blending, distilling, fermenting as a separate batch, and so on. In this test, a single press fraction at 50-pound pressure was done.

Pomace: this is the leftover pulp, seeds, and berry skins after pressing is complete. Some Winemakers call it a pomace cake. It is most often returned to the orchard and composted into the soil as an amendment to soil health.

Day 11: Secondary Fermenter: Test Batches

Please follow along with the video to see test batches being racked into secondary fermenters called carboys. Wine is considered ‘food’ from a health and safety standpoint and all safe food practices must be followed.

Remember that these are test batches, and the big batches will be conducted on a much larger scale, including pumps and large hoses instead of siphoning, professional 1,000-2,100 L+ fermenting tanks, etc. The test batches allow for verification of defined processes, including lab work and food safety, and to become familiar with all equipment.

Racking Terms

Racking: the process of moving wine from one container to another to leave the lees behind.

Lees: the sediment at the bottom of the wine, mostly composed of dead yeast cells, wine skins, some protein, seeds, and precipitate from chemical reactions (such as the chemical “salts” formed like calcium malate).

Secondary Fermentation: recap: the primary fermentation is the formation of alcohol in the primary fermenter until the Brix is somewhat close to finishing, usually around 5 to 8 Brix (or 1.010 to 1.025 sp gravity). At this point, the foaming and aggressive action is slowing down, and the carbon dioxide can no longer be depended upon to blanket the top of the wine, protecting it. So we rack into the secondary fermenter to finish the fermentation, use up all the sugar, clean the wine off the lees, and stabilize, clear and polish the wine.

Second Fermentation: this is not to be confused with secondary fermentation (although many people use the words interchangeably). In fact, true second fermentation involves no yeast at all, and relies on the action of a bacteria to process the malic acid. The stylistic goals of the Winemaker will determine if MLF (malolactic or second fermentation) will be conducted at all. Like yeast inoculation, wine can be inoculated with a special bacteria, called malolactic bacteria, to perform this work.

Carboy: shown in the video as the glass rounded vessels to which the wine is siphoned, usually used only as secondary fermenters as they will overflow if used as primaries.

Fermentation Lock: a finely engineered system which prevents the back flow of air and CO2 into the wine, allowing the by-product CO2 to escape and keeping the wine free of oxygen, literally locking the fermentation off-gassing into a one-way system.

Days 12 - 21: Fermentation Complete and New Batches Started: Test Batches

Fermentation of Initial Test Batches Complete: Once the first 6 batches were finished fermenting, as indicated by a specific gravity below 1.000 (or a negative Brix), the final processes leading us to a polished and quality consumer-ready product were begun.

Decision to Start New Batches: In the interim, a decision was made to start an additional 6 batches and re-work the process to achieve less acidity, reduce astringency and heighten colour. Specifically, it was determined to press earlier, mixing in sugar later, and other time-related activities that would affect the finished product.

August 2020: Finalization of Test Batches and Starting Large Scale Fermentation

Following literally dozens of test batches, some of which were discarded and some of which will be blended into the final large batches, the decision was made to initiate full-scale fermentation, starting with 2020s harvest in late August 2020, and then using 2019s frozen fruit in late September 2020. You can follow along with our full-scale fermentation in our next posts.

New Terms

Specific gravity: Specific gravity (referred to as Brix) is the weight of the fermented wine as compared to the weight of R/O (or distilled) water. Specific gravity of 1.030 is 1.03 times the density of water. Since alcohol in a solution will cause that solution to weigh less than water by itself, the final specific gravity of the wine can also be used to determine the alcohol content of that wine, particularly after a small sample is distilled. Specific gravity in the below 1.0 range (such as 0.996) is a somewhat unreliable indicator of the completion of fermentation.

Fermentable sugars: Must contains several sugars. When the sugar content of the wine is measured to determine if fermentation is complete, a Winemaker will say this is less than a gram or two per liter. There are sophisticated tests to determine if the remaining sugar is fermentable sugar. The remaining unfermented sugar is called residual sugar. To amend the wine with additional sugar, the yeast must be taken out of the wine, or inactivated. Otherwise, fermentation could re-start in the bottle and cause C02 bubbles and possibly burst the bottle (in the case of sparkling wine and beer, this sugar addition is done deliberately in a controlled fashion, so the bubbles are produced).

Ferment on fruit: the choice to press early (before fermentation and after a short maceration) is a stylistic one, dependent on the nature of the fruit and the goals of the Winemaker. We have found that Haskap tends toward too much acidity and rougher character extraction if macerated too long or fermented on much fruit at all. In fact, we’ve experimented with variations in the amount of fruit left to ferment, all the way to fermenting on pressed fruit juice only. This may change depending on each year’s harvest, which will be assessed separately.

Mid-palate body: the middle of the mouth and tongue where the sensation of acidity and astringency are perceived, as well as the less defined ‘body’, which is often attributed to polysaccharides, glycerol, and other less defined attributes in wine.

Maceration: fruit or wine liquid left in contact with the crushed fruit, extracting skin colour, tannins and possibly acidity. The decisions to prolong cold soak maceration and/or maceration following fermentation are dependent on fruit type and stylistic choices.

TA: titratable acidity is the measure of acids in fruit juice and wine, using a laboratory process called titration. In theory, the value is compared to tartaric acid in grapes, although fruits other than grapes contain none.

Carbon Dioxide: Dangers of CO2 in the Winery (June 8, 2020)

From the chemical formula:

C6H12O6 → 2 C2H5OH + 2 CO2

sugar yields alcohol plus carbon dioxide

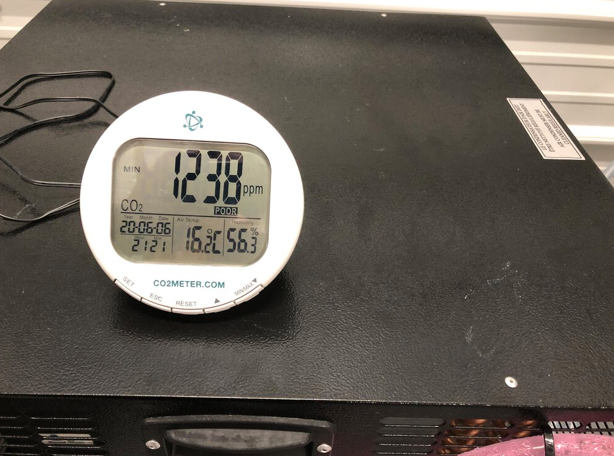

It’s abundantly clear that the process of fermentation produces quantities of CO2, a colourless and odourless gas, which at specific parts per million in room air constitutes a danger to the health and safety of winery personnel. CO2 is twice as heavy as air; therefore, it will sink to the bottom of a room forming potentially deadly pools of gas that will displace oxygen (O2). CO2 has been found to settle in corners of rooms and in areas that are generally undisturbed with low ventilation. The presence of CO2 is not known until symptoms of exposure are experienced, or unless there is a CO2 meter. At peak fermentation the volume of CO2 produced in 24 hours may be 10 to 15 times greater than that which occurs naturally in air (normal room air has 350 ppm). Without adequate ventilation, CO2 can displace oxygen and produce an atmosphere that is both high in CO2 and low in oxygen. With a 1000 L tank in peak fermentation, it was clear to Bee & Thistle that the threshold for safety would be reached quickly.

It’s amazing how much CO2 is produced by the fermentation of sugar into alcohol. CO2 is measured by weight; in fact, it has been stated that when 1 pound (0.45 kg) of CO2 is produced, it creates 8.7 cubic feet (or 0.246 cubic meters) of CO2 . So then, that same amount of CO2 will raise the parts per million (ppm) of an average 1,000 cubic foot room by 1,000 ppm.

A few facts to understand:

Carbon dioxide (CO2 ) is a toxic gas at high concentration.

1,000 ppm: breathable and not dangerous.

5,000 ppm: over an 8-hour shift, this amount of CO2 would be the maximum allowed by OHS (Occupational Health and Safety).

10,000 ppm: breathing rate increases slightly.

30,000 ppm: breathing rate increases to twice the normal rate and a person will likely experience impaired hearing, headache and increased blood pressure.

50,000 ppm+: (STEL) short term exposure limit of greater than 5 minutes; Imminent Danger to Life and Health (IDLH). Breathing increases to approximately four times the normal rate, symptoms of intoxication become evident and slight choking may be felt.

60,000 ppm+: no exposure permitted as doing so could cause immediate loss of consciousness leading to death.

Bee & Thistle Winery has several safeguards in place to monitor and mitigate the hazards of CO2 exposure:

CO2 monitor between fermenting tanks, nearer the floor level as CO2 is heavier than room air

Venmar ventilation system, which draws air out of the room and replaces it with warmed outside air, maintaining the CO2 level below 2000 ppm.

An informational chart outlining the dangers and health effects of CO2.

Instructional material provided to all personnel as to what circumstances may result in high CO2 levels, how to monitor the CO2 situation, the limitations of mechanical ventilation, and what to do if the readings are high or unobtainable. There is a written policy to follow, which also includes use, care and maintenance of the Venmar and the CO2 monitor, and emergency measures and procedures to follow

Carbon Dioxide: Benefits of CO2 in the Winery (June 16, 2020)

Despite the bad reputation of CO2 and its effect on personnel safety, CO2 is also a friend in the winemaking process. Managed properly, a layer or blanket of CO2 on top of wine will prevent contact of wine with air. Wine exposed to air will cause many issues, including oxidation, increased activity of certain non-beneficial microorganisms and production of other undesirables (such as high volatile acidity—aka vinegar smell and taste, and chemical smells and tastes).

To protect the top of the wine when CO2 production slows down, we have a strict policy of topping up in carboys as far as possible with floating lids in tanks over 100 L. This lid prevents air from contacting wine after the production of the CO2 blanket is reduced - which occurs after a Brix of about 8, or a specific gravity of about 1.030. In addition to floating lids, we also use Nitrogen to assist with our oxygen management practices. In these videos, Peter explains the processes.

Pitching of Yeast: Official Start of Wine (June 19, 2020)

Every wine has an official start from a legal standpoint. Wine is not wine until the first drop of alcohol is made. Therefore, the official start of wine is the Pitching of Yeast.

Historically, Winemakers called yeast addition ‘pitching’. It is unclear exactly how this term started:

History and Etymology for pitch. Noun (1) Middle English pich, from Old English pic, from Latin pic-, pix; akin to Greek pissa pitch, Old Church Slavonic pĭcĭlŭ. Verb (2) Middle English pichen to thrust, drive, fix firmly, probably from Old English *piccan, from Vulgar Latin *piccare

There is a clear timeline that wWinemakers must follow to optimize the yeast addition. Conditions for the Pitching of Yeast must be optimal; they include proper temperature, nutrition, and acid levels. We also add the yeast at the correct time with relation to other amendments. In addition, yeast must be fresh and stored properly. We always ensure expiry dates are double-checked and that the yeast is stored according to package directions to maintain yeast cell integrity.

There is a defined protocol in yeast preparation, which includes hydration, as well as supplying the correct starter yeast nutrition such as Go-Ferm (TM). Hydrating of commercial yeast is a very important step. Unhydrated yeast will not multiply properly; efficient multiplication of yeast is crucial to cell numbers which support fermentation. Also, preparation includes specific temperature control at each step, including ensuring that the fruit must temperature is high enough. All the protocols are followed to decrease yeast stress and enable quick and thorough yeast cell multiplication so they can work efficiently and expeditiously continue along the fermentation cycles.

The following video shows the actual Pitching of Yeast after all the yeast preparation was completed. Collin and Peter capably work together to ensure the steps are followed correctly.

How Do We Know When Berries Are Ready For Harvest? (July 13, 2020)

Winemakers who are responsible for deciding the harvest date of a vineyard rely on visual, taste, aroma, and chemical parameters to optimize the fruit for the style of wine they plan to make. Since we grow our own fruit for our wines, we have the pleasure of sampling and making such decisions in a more leisurely fashion.

Currently, our orchards are divided into 6 “blocks”.

Optimally, I would take a representative sample from each block every day or two; then examine, taste and chemically analyze. Treatment of all test samples is identical:

handpicked at random intervals throughout the block, including sun sides and shaded sides, top and bottom of random plants

washed gently in cool water, air dried, and frozen 24 hours in a Ziploc™ bag

crushed and treated with pectinase and glucosidases (aka enzymes) as per wine protocol (allowed to macerate for 6 hours)

pressed for juice

Brix, pH, and TA (titratable acidity) are measured, and colour and aroma assessed

ratio of 35-40 percent juice and 60-65 percent water with Brix adequate to obtain a final Brix of 20.5 to 22.0

assessed again for colour, pH, TA, taste, and aroma

Block 1: Home Acre Indigo Gem and Berry Blue: with a 4:1 ratio 7 rows 45-65 plants each 7 years old

Sample 1: July 8, 2020

Weight 360 g: Brix was 12.5, pH 3.0, pH and TA more acidic still; the decision was made to wait 3 more days and test again as the Brix was not ideal, and the product still a little acidic and tart for wine, although these kinds of berries make excellent jam and toppings! One procedure we follow when testing berries for ripeness is cutting them open and looking for solid red/indigo colour throughout plus assessment of the seed maturity. In this sample you can see that the berries aren’t optimally ripe; if they were, they would not have any red spots and the colour would be indigo blue throughout.

Sample 2: July 11, 2020:

Weight 360 g: Brix was 13, pH 3.1, less acidic. Again, we need to wait a little longer. Berries tasting sweeter and looking ripe.

Sample 3: July 13, 2020

Weight 360 g (left sample), the right is another sample from Block 3a. You can already see that the colour is deeper and more uniformly indigo blue. This sample has a Brix of 14 and is indicative of being nearly ready for harvest. The taste is optimal, and the colour of the cut berry is also uniformly ripe. The seeds are starting to look ripe as well. We will be starting Block 1’s harvest on July 15.

Block 2: Home Acre Tundra and Berry Blue: with a 4:1 ratio 6 rows of 65 plants each 7 years old

Sample 1: July 13, 2020

The Brix of each sample is checked, along with other parameters to determine suitable harvest time. During the lab assessment, the dilution ratio of each sample to provide optimal product to ferment is established. For example, this sample was diluted 35%: Brix 14.2 juice, with 65% Brix 26 water (sugar added) and the pH, TA, and taste/aroma were determined to be optimal.

For example, if I want a final Brix of 21, I will make my water at Brix

(35 x 14.2) + (65 x X) divided by 100 = 21

X = Brix of 26

Sample 2: July 15, 2020

Block 3a: North Orchard Indigo Gem and Berry Blue, some Smart Berry Blue and some Aurora: 12 rows, 8 with 205-10 plants each and 4 with 120-170 plants each, the South 50 plants of Rows 13 to 20 are also included since they are prone to both drought and flooding and are more stressed than Block 3b. Most are 5 years old, some younger at the roadside (4 years old); some mole damage and susceptible to flooding or drought and wind. Seems to ripen more quickly. Considerable weed pressure in this block too. General stress.

Sample 1: July 13, 2020

Sample 2: July 15, 2020

The second sample indicated this block was ready for harvest on the 15th, with a Brix of nearly 15.

Block 3b: North Orchard Indigo Gem and Berry Blue, some Smart Berry Blue and some Aurora: 4 rows mature 6 and 7 years old, 210 plants each. North 155 plants of Rows 13 to 20. Healthier and protected from the wind. Seems to ripen less quickly than 3a, but more quickly than Block 4 (which is primarily Tundra and later anyway). Less weed pressure and healthier plants than Block 3a. Some boron deficiency noted.

Sample 1: July 13, 2020

Sample 2: July 15, 2020

The second sample indicated this block was ready for harvest on the 15th, with a Brix of nearly 15.

Block 4a: North Orchard Tundra and Berry Blue, some Smart Berry Blue and some Aurora. Healthy, protected and stress-free plants. First 12 rows, and North half of last 10 rows. Mostly mature 6- and 7-year-olds. Some evidence of boron deficiency. Little stress otherwise.

Sample 1: July 14, 2020

Sample 2: July 16, 2020

The second samples were more than ready to harvest, at a Brix of nearly 15, and definitely great colour throughout the berry.

Block 4b: North Orchard Tundra and Smart Berry Blue, more Aurora here. This area is the top of the hillside South of Rows 13-22, which had drought stress in the first 3 years, although is currently thriving. Plants are mostly 5 or 6 years old and now healthy, with the area of the hill having better drainage in this rainy season of 2020. Some evidence of boron deficiency.

Sample 1: July 15, 2020

Sample 2: July 17, 2020

Again, samples were done as indicated. We then got busy with harvest and, with the final samples, decided the order of harvest.

It was a good exercise, and with the sample notes in hand, it was easy to decide which blocks to harvest first. We also label buckets with block numbers and areas so that we can plan for additions and correct wine making decisions which will optimize the flavour, aroma and profile of each batch according to the berries we harvested.

Chiad Fhion Haskap Wine - 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 (post created August 21, 2020)

Following several months of test batches and practicing our routines, we were finally prepared to initiate full-scale fermentation. Exciting times!

Vintage 2020

Our Haskap wine journey was started with 2020’s frozen July harvest. Vintage 2019 was started a month later from stored fruit.

Growing Season Report: 2020 was a bit of a challenging year for Bee & Thistle Orchards, with a delayed spring and late bud break in addition to temperatures being suboptimal. Flower drop following pollination was in early June, with veraison (turning blue) of the berries occurred on June 25. Using that date, we predicted harvest readiness on July 15, assuming adequate rainfall and sunshine. With an excess of rain and suboptimal sun hours, the berries were a little high in malic acid, but average Brix was close to a respectable 15. Colour in the berries was very good, with a deep crimson indigo throughout the fruit. Therefore, harvesting commenced as predicted in mid-July.

Fruit Available Report: We harvested nearly 12,000 pounds of Haskap in 2020. See our post on how we knew when the berries were ready for harvest, as well as a video of our 2020 harvest: the fruit will be fermented in small batches of 1000 L per batch until all is gone!

August 21, 2020

A large quantity of haskap in pails were brought from the freezers and thawed, then crushed into the large primary fermenters. Sugar and water were added, with amendments and adjustments done as well. The berries were macerated for a time with added enzymes, after which they were pressed and returned to the primary fermenters to ensure that fermentation would proceed unimpeded before transferring to the 2,100L tank. The temperature of the juice was adjusted to permit the yeast to multiply and start ferment stress-free.

August 22, 2020

Yeast was pitched; we chose another select yeast for this batch since we intended to ferment in a glycol-chilled controlled temperature tank. Cooler temperatures protect the aroma and fruity flavours with this yeast noted for production of fresh fruity aromatics and true-to-fruit profiles. I also made judicious additions to accent the fruitiness and bring out the natural characteristics of Haskap, optimizing both colour and flavour. Yeast nutrient is a requirement for most non-grape fermentation; needed additions are carefully calculated based on specific in-house lab testing. Many wineries try to argue that wine should not be made in ‘lab’; I personally feel this is a narrow-minded comment meant to discredit our work. To assume that fruit other than grapes (and indeed, many grapes are lacking as well) has sufficient nutrients to support that yeast is also foolhardy. Supplemental yeast nutrient is almost a ubiquitous practice since fruit such as Haskap simply does not have sufficient yeast available nitrogen to support continued fermentation. I, for one, will not throw out a batch when a simple lab test can provide me with information I need to confidently proceed.

August 25, 2020

After observing and testing thrice daily, it was determined that our fruit aroma profile would benefit from maintaining the temperature of the must a bit cooler; therefore, the must was pumped into the large glycol controlled 2,100L tank to prevent its overheating and destroying our work to date. The tank has a sampling port, and the wine was tested and followed closely until fermentation was completed.

August 30, 2020

Haskap Wine Vintage 2020, 2,000L was progressing very well with temperature-controlled fermentation to accent the fruity aromas and flavours inherent in Haskap. It took about 2 more weeks to finish fermenting and then the work of stabilizing, finishing, subtle adjustments, and aging began.

September-December 2020

Haskap Wine Vintage 2020 tested as having completed fermentation in mid-September, as expected. We racked off the lees at this time, added a bit of adjustment products, and decided on the plan of action going forward. Wine samples will be taken weekly until it is determined that the wine is properly developed to its maximum potential. This is expected to take between 2 and 4 months, with anticipated finishing around Christmas or early January. The wine is predictably young, raw, and unaged. However, the aromas are clear and there is no evidence of untoward activity or contamination. Finings will be used when appropriate or if indicated by lab testing and bench trials.

Pre-bottling, December 2020

Haskap Wine Vintage 2020 was filtered and back sweetened. Final filtering straight into the bottle will be a sterile filtering as per good winemaking practice, which clears both bacteria and yeast, but retains all aromatic and taste elements. No one wants a cloudy bottle of wine and few consumers like sediment in their wine either, although fining is as important as filtering to achieve stability.

Next batches, January and February 2022

From January 15 to February 15, 2022, 3000 L of Haskap Wine Vintage 2020 will be fermented and processed as planned above. The flavour and profile of this fruit harvest (from frozen fruit) is expected to be as award-winning as our initial batch, which garnered 92 points at the New York International Wine Competition in 2021. The processing is similar, with slightly more whole fruit retained as it was noticed that there was perhaps excessive bitter tannin release from the heavily crushed and pressed first batches in 2020, which had to be fined out. Perhaps we can avoid excessive processing and extra fining by a little more attention to early stages of the fermentation and handling of fruit.

Instead of flooding the whole tank with oak, which is a bit risky, we decided to trial oak in carboys. We will add that at a very precise ratio as determined by the bench trial. And finally, upon target-market analysis, it was determined that most target consumers prefer their red fruit wines to be semi-sweet to sweet, so we are testing with various amounts of back-sweetening sugar syrup as well. Only a very small segment of fruit wine drinkers prefer dry fruit wine, even if they prefer dry grape wine. A smaller quantity of dry Haskap wine is being trialed and will be introduced in fall, 2021 if found to meet our stringent quality standards.

Following some additional fining to smooth out the edge of astringency, and several judicious filtering (rough and polish), we added a small amount of colour stabilizers.

Bottled: End December 2020 and Mid January, 2021

Released Date: End January 2021

Sold Out first batch: April 2021

More available from subsequent batches: October 2021

June 2021

Batch 2, 2020: Started June 2021 1000 L, will be made into fortified dessert wine, Haskap MIST™, and regular Semi-Sweet and also Dry table wine; progressed much the same as batch 1 (2020) and finished fermentation in a timely manner. Different yeast utilized with slightly different methods to maximize flavours. A small quantity was trialed to fortify early to stop fermentation and put in a carboy to mellow and age a little. If this is successful, a new batch will be started and dedicated to strictly fortified dessert wine and bottled in 375 mL flint Bordeaux bottles with Tcaps and security logo strips.

October 2021

Bottled Haskap DRY 20 cases.

Vintage 2019 (Aged)

Our next Haskap wine ferment was started with 2019’s frozen harvest.

Growing Season Report: 2019 was a bit of a challenging year for Bee & Thistle Orchards, with a delayed spring and late bud break in addition to colder than normal temperatures right up to harvest week. Traveling plans and logistics had our harvesting a little sooner than optimal, therefore, the fruit will be handled with an eye to reducing the less than ripe character. We also had an excess of rain, and the fruit was a bit less concentrated, with an overall Brix of just around 14. Colour in the berries was very good, although we did determine we would need to macerate and ferment on these berries a bit longer to release the tannins and aromas and to maximize colour extraction.

Fruit Available Report: The winery has purchased 3 pallets of fruit from the Bee & Thistle Orchards. One pallet was used for this batch and the other two will be used in late December after the Rhubarb wine tanks are free.

September 25-26, 2020

Pails of Haskap were brought from the freezers, thawed in pails, crushed into the large primary fermenters, sugar and water added, with amendments and adjustments done as well. The berries were macerated for approximately 24 hours with added enzymes. Fermentation was monitored closely thereafter.

September 30, 2020

After fermenting on berries for a longer period to maximize elements desirable to the finished wine, (with thrice daily punch downs), the must was pressed and the resulting ferment pumped into a 1,000L tank, with several smaller carboys utilized for topping up and testing purposes in conjunction with the bulk ferment. The ferment was allowed to progress to completion in a glycol-chilled tank set a bit cooler, with daily monitoring, Regular checks were performed, and parameters were measured.

Late October 2020

The must was racked off the lees once again, with parameters re-adjusted as determined by in-house lab tests. The fermentation was completed in about 4 weeks and, as with 2020’s vintage, the tank aging process is initiated and underway.

Each time we rack, and once a week during tank settling, samples are taken and assessed. The sample was clean, had no evidence of negative odour, observed to be somewhat cloudy due to unsettled yeast; with the addition some sugar, tasted pleasing for an immature unaged, unfiltered and unsettled wine just finished fermenting to dryness. The astringency/acid/alcohol balances are very good. I am currently doing some smaller carboy testing to determine if this wine could benefit from a little addition of oak chips. The 1000L tank of Haskap Vintage 2019 is being held at 55F (12.5C) for settling and tank aging.

December 2020

Assessments continue Vintage 2019 Haskap, with all pointing toward a favourable outcome and an aromatic somewhat complex wine as compared to Vintage 2020 Haskap. We are attributing this to an initial longer ferment on the fruit, as well as to the specific attention paid to careful earlier racking following fermentation to mitigate negative flavour and aroma and allow the wine to age with freshness and fruit-forward attributes. Frequently, grape Winemakers will age on lees (sur lie²) but in the case of immature fruit, this practice would not be advisable. We also did a few minor adjustments, and we will assess the possibility of aging on a little oak chips to accent the fruit.

January 2021

Very successful attributes are noted whilst this wine continues to age beautifully. Oak chips and final filtering and finings with appropriate products are in progress.

²sur lie: French ‘on the lees’: aging wine on lees; this practice keeps the wine in contact with the dead yeast cells, adding flavours, aromas, depth, and complexity. If fruit is immature or has evidence of Botrytis, this practice would not be advised as it would concentrate the negative attributes instead of accenting the positive ones.

Tank aging to May 2021: Tank aging to develop flavours and give the customer a chance to taste the more aged Haskap wine.

Bottled May 2021: 70 cases.

Released for sale: May 2021

Sold out: July 2021; more made in a new batch below, available August 2021

New batch: late January 2021

CF5 2019 Vintage: 2000 L started with a new yeast and has progressed. This yeast is noted for high aroma producing capacity, and easily captures the essence of Haskap at a lower fermentation temperature. Wine was fermented ‘on fruit’ until Brix 8 or sp.gr. approximately 1.030 to ensure maximum fruit flavour extraction. Again, we chose the yeast derivative enhancer dedicated to more immature fruit. This time we dared to start at a higher alcohol potential Brix, which should give us a finished alcohol of closer to 12-13.5%. This would be the ideal starting point for our new product, Haskap MIST™, requiring less wine and allowing for the addition of more juice! Our Haskap MIST™ product has a proprietary secret ingredient list, which definitely includes a good amount of real Haskap juice and provides a real punch of flavour.

Mid February 2021

The fermentation of this lovely batch of wine is completed. Finishing tasks were performed (including racking and rough filtering), while we opened our winery for sales! This will probably be the busiest season in the lifetime of our winery.

End February 2021

Because we were very busy with the first month of winery opening and sales, the decision was made to allow this batch to tank age a bit longer, which will allow us the opportunity to finalize our plans for it. Since it is pleasing when quite dry, we are going to experiment with several options and will possibly divide this batch to best determine our course of action. And a little tank aging never hurt a wine. Of course, the parameters will be closely monitored, and adjustments made as necessary.

Early March 2021

We’ve added another 1000 L batch of the 2019 berries to the primary tubs, and will blend these two CF5s together once they are both finished, to allow them to age blended in the 2100 L tank. They are being treated in precisely the same way. Then we can opt to use some for Haskap MIST™ as required and finalize our plans.

Mid March 2021

We’ve filtered and done preliminary adjustments to the first batch, including addition of some select products to enhance the fruit-forward attributes. This batch is testing at relatively high alcohol (13%) and will be blended with the lower alc/vol (12%) second batch. Balance in fruit wine is achieved by balance in alcohol as well as many other things, and this level of alcohol is just a little higher than optimal for a balanced taste test on 7-week-old wine; we’ll blend and adjust until we get the level we want. In saying that, the other attributes, including flavour, colour, aromatics, and finish, are very good to excellent. This gives me confidence this is a very nice batch and will only improve upon further aging and slight adjustments to accent the natural flavours and aromas of Haskap, and to bring out its potential in wine.

Mid April 2021

Blended CF5i and CF5ii: 12.5% alc/vol

To June 2021: Tank aging and final adjustments/finings

Bottled: 225 cases, early July 2021

Released to Market: August 2021, delivered a quantity to Alberta as well.

New batch: June 2021

CF7 2020 + 2019 Vintage: 1000 L started with a new yeast and has progressed. This yeast is noted for high flavour producing capacity, more mature fruit, and easily captures the essence of Haskap at a lower fermentation temperature. Again, we chose the yeast derivative enhancer dedicated to more mature fruit. This batch should work out well for proposed Haskap Dry and possibly some more Haskap MIST™ and a new product, Haskap Fortified at 19.5% alc/vol with the addition of some neutral grain spirit, sweetening and final adjustments.

July 2021

The fermentation of this lovely batch of wine is completed and the aromas and tastes are awesome!

End August 2021

Aging time—the parameters will be closely monitored, and adjustments made as necessary.

The other attributes, including flavour, colour, aromatics, and finish, are excellent. This is a very nice batch and will only improve upon further aging and slight adjustments to accent the natural flavours and aromas of Haskap, and to bring out its potential in wine. Alc/Vol before back sweetening has a good balance and with appropriate tannins and a little oak, this will be a great new product for Haskap DRY.

Plans to Bottle:

Haskap DRY (with little sugar added 10 g/L so sweetness level 1), bottled 20 cases October 2021, released November 2021

CHIAD FHION Haskap Regular our brand award winning wine with our normal sweetening protocol

THE ABBEY Haskap Fortified Dessert Fruit Wine, preliminary testing SLGA approved 19.5% November 2021

New batch: mid July 2021

CF8 2021 Vintage: 2200 L started directly from harvest in mid July, with amazingly ripe fruit and a very advanced flavour profile. Again, we chose the yeast derivative enhancer dedicated to more mature fruit and the appropriate yeast as well. This is a large, well-developed batch that should do great things! The summer was extremely hot and a little bit of water restriction due to lack of rain does develop very flavourful fruit with a good amount of natural sugar! We did lose a quantity of this harvest due to a premature hailstorm on June 7, just as fruit was beginning to set.

Mid August 2021

Fermentation completed.

Aging time will begin soon - the parameters will be closely monitored, and adjustments made as necessary.

The other attributes, including flavour, colour, aromatics, and finish, are excellent. This is a unique batch and will only improve upon further aging and slight adjustments to accent the natural flavours and aromas of Haskap, and to bring out its potential in wine.

Sept-December 2021

Tank aging at 12C. This is being sampled weekly and continues to develop beautifully with a unique flavour profile likely dependent on the hot dry year we had.

Chiad Fhion Haskap Fruit Wine CF8

Haskap MIST™ batches MT 5 and MT6

2 batches of The Abbey Fortified Haskap Dessert Wine HF1 and HF2

600 L distilled for the fortified, both The Abbey and Kinlochaline.

Jan-March, 2022

2200 L of CF9 were fermented and left to age in tank through to June 2022, using some of the remainder of 2020s fruit from frozen storage. This batch will also be multi-purposed as was CF8, into Haskap DRY, regular Chiad Fhion Haskap, Fortified The Abbey and Kinlochaline, as well as Haskap MIST™.

Additional batches were made throughout late 2022 and into 2023 and 2024.

Several new products are being trialed as well. One exciting release planned for late Spring, 2024!!

Rhubarb - 2019 to 2021 (October 20, 2020)

Rhubarb Wine General Notes

From a winemaking perspective, Rhubarb is a little difficult to work with. Firstly, there is a lot of pectin in Rhubarb, which will cloud the wine if allowed to persist untreated. Therefore, calculated generous quantities of an enzyme are added to break down the pectin and allow the wine to clear more readily upon completion of fermentation. We also add another specific enzyme which breaks down the sugar molecules attached to the aroma molecules, allowing for their expression and release of gentle aromatics specific to Rhubarb. The second issue with Rhubarb is high acidity, but not all rhubarb has this issue; German Wine Rhubarb tends to the more alkaline end of the acidity spectrum and even occasionally benefits from a little acid addition! Portions of some varieites Rhubarb fruit are deacidified to an alkaline level (or acidified depending on variety), and added back to the original mix, achieving an ultimate overall calculated specific end goal for my stylistic choices in acid balance/tanginess.

After the addition of calculated nutrients and yeast enhancers according to specific lab tests, the ferment is conducted on fruit in tubs for a few days, at which time we press out the juice and discard the pulp as compost for the orchards. We may also experiment with other products if the tests show increased complexity and enhanced fruit on the palate.

Rhubarb Wine Vintage 2019

From frozen German Wine Rhubarb, Rhubarb wine vintage 2019 was started in late May 2020. We began with approximately 800 L.

Yeast Selection: Specific yeast to address the cool to cold fermentation we want to conduct. Specific yeasts are not mentioned due to proprietary reasons.

Starting Brix: with a goal of approximately 12% alc/vol. Rhubarb wine is softly citrus and aromatically tropical; we did not want the alcohol to overwhelm the unique expression of those notes. A small amount of adjustment with other constituents will be made.

Batch 2020 Haskap was used for blending in a small amount, with a beautiful peachy pink colour resulting (after a Bench Trial). The taste is unique and accents the Rhubarb profile in a very pleasing way. This blend was allowed to meld. Heat stability, acidity check, fining and sweetening trials were performed in house. From the results of those trials, we fined with selected products, settled, and filtered through the stages, and back sweetened according to taste and desired profile.

THE COLOUR STARTS OUT VIVID BUT AS WINE DEVELOPS, IT SUBDUES

Rhubarb Wine Vintage 2020

We harvested the German Wine Rhubarb in mid-June 2020 and froze the fruit for two weeks. Frozen fruit is easier to macerate, and it releases its juice more readily than fresh. We began with approximately 800 L of Rhubarb wine vintage 2020.

Yeast Selection: Select yeast (proprietary secret) at a generous 25 g/HL. This yeast was selected due to its ability to express aroma and citrus/tropical fruit by fermenting at a decidedly low temperature. The tanks were maintained at 15-17 C with the use of glycol chiller plates.

Starting Brix: goal of approximately 11.5 - 12% alc/vol. We maintained the ferment at 15-17 C throughout and quickly noted the grapefruit and citrus notes, even early on before fermentation was completed. This flavour profile is expected to develop through the tank aging in September and October. This batch also received a small number of tweaking adjustments as suggested by the tests we did in May.

Specifically selected strain for the inoculation of cold ..must (even as low as 10°C/50°F) and for its aroma preserving capabilities.

Wines produced with select yeast are known to promote the following aromatics: citrus, grapefruit, apple and peach.

A fast fermenter with low nitrogen requirements, the recommended temperature range is between 13–17°C (55–62°F).

Select yeast is tolerant up to 15% (v/v).

The wine was allowed to settle and mature a bit before being blended with a small quantity of Haskap, which was trialed in the lab and found to accent the attributes of the German Wine Rhubarb, as well as providing a bit of mystique to the final profile.

The resulting blend was melded and aged for a further time, during which time we also fined and filtered similarly to LA2019, and back sweetened to a slightly lesser degree. Since the profile was a bit more intriguing, we did not want to mask the astringency and development of the tannin, which had complexed nicely over the course of tank aging and will further develop in bottle. We also balanced the acidity profile. The colour is just a hint stronger than LA2019, which we expected. Very nicely balanced wine, a bit tart and a bit sweet (but not too much), with classic Rhubarb palate and nose, and tropical overtones.

Rhubarb Wine Vintage 2021

June 2021

Loch Aline Rhubarb with Haskap 2021 started off from a very hot dry harvest condition, but despite the challenges of the year (including hail on June 7), the fruit has higher than average Brix and a very favourable flavour profile. Enough was collected to prepare a 1000 L batch, with the usual expected fermentation time allowed. The nutrients, yeast, and stylistic choices for this wine are similar to those used for 2020’s wine, which had a very promising and award-winning taste profile, garnering 90 pts at NYIWC (Bronze Medal), so it was decided to adhere to that plan. With a few tweaks to possibly create an even better batch, aiming for a gold from this batch!

July and August 2021

Fermentation completed and aging began. Very lovely colour, a bit pinker than either 2019 or 2020’s batches (probably due to the heat and early ripening), with a slightly more varietal rhubarb profile too! Promising.

September and October 2021

Aged in a tank. This is definitely a lovely wine, with true varietal flavour and very clean crisp. It will make a lovely Rhubarb DRY, with just a slightest hint of sugar at 10 g/L. A further portion will be sweetened more so, and be similar to 2020's award-winning vintage.

October 24, 2021

Bottled 50 Cases Loch Aline 2021

Bottled 40 Cases Rhubarb DRY

January 2022

Remainder of 2021’s German Wine Rhubarb started fermenting, with an expectation of bottling in May/June. Same flavour profile, yeast, and conditions as the previous batch done in June, 2021.

April 2022

Bottled very nice batch with high colour. Split between Rhubarb Dry and Loch Aline Rhubarb 2021 Batch LA4.

July 2022 into 2024

Several more batches are planned or underway now that our basic processes are finalized and modified.

A Day in the Winery (October 30, 2020)

Specific Events